Welcome to Big Think Books, your direct line to the books and ideas that shape our world. I’m Kevin Dickinson, and this month, we’re looking at history books that bring the past into a new perspective. Big Think regular Jasna Hodžić also joins us to discuss a book that had her asking, “What actually ‘am’ I?” And we wrap things up with some of the strangest books ever written.

Next month, we’ll examine the 80-year legacy of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and atomic power. Stay tuned!

We are the 99% (of history)

I grew up a military brat, and one year when I was in grade school, my family moved to a market town east of London called Thetford. While living that quaint English lifestyle, my class took a field trip to a historical village.

You’re likely familiar with the concept: Kids dress up in era-appropriate tunics and breeches — cotton instead of wool, but still — and actors pretend to be peasants, clergymen, and officials while teaching about life half a millennium ago. Basically, what you’d get if PBS put on your local ren faire.

This particular village was different, though. They didn’t just lecture us about history; they put our newly minted medieval butts to work. My classmates and I kneaded bread loaves in wooden troughs and hung sagging cheese clothes heavy with curds. We dunked cords in tallow and beeswax (or some equivalent) over and over and over again to make candles.

It obviously wasn’t a perfect replica of medieval living — a noticeable lack of dysentery being the obvious giveaway. But the experience proved a tangible, kinetic way to learn about a time in history, and it connected me with the people who lived through it in ways few history lessons can.

In fact, the experience stands in direct contrast to much of my schooling, which typically revolved around stale recitations of the historical big three: important names, significant dates, and pivotal events. These were ground into us to the point that you could always make out a ghostly Abraham Lincoln, 1492, or Battle of Trafalgar lingering on the whiteboard. Fill in the correct bubble on the test, and you were a bona fide history buff.

I bring this up in this newsletter (ostensibly) about books because it relates to a trend I’ve noticed in the history section of my local bookstore.

For the longest time, the genre was content to be a continuation of your standard school lesson. Whether crossing the Rubicon with Caesar in 49 BC, examining the industrial slaughterhouse of Stalingrad in 1942, or unearthing every detail of a dead president’s life in a 500+-page doorstopper, popular history books liked to focus on great men and grand moments. The stories of everyday people living their everyday lives rarely factored in, and when they did, it was often as background for the big three.

That said, I haven’t done a rigorous survey here. This “trend” may be as much a change in my own reading habits as a shift in the books authors are writing or the focus of academic studies. (D: All of the above?) Whatever the case, this month Big Think featured several books that showed me why it’s essential to balance great-moment history with a richer understanding of how the ancestral 99% shaped history in their own way.

Chief among these was Dinner with King Tut. In it, author Sam Kean explores experimental archaeology, a trend in which practitioners attempt to recreate the past to gather data and test hypotheses. Similar to my historical village visit, Kean performed all manner of tasks the way our ancestors did. He fired a medieval cannon, tanned hides with urine and brains, and played an Aztec sport in a leather loincloth.

Why? As he told me, “It’s fun to read about kings and generals and the like, but if you’re immersed in the life of an everyday person [from the past], it’s more relatable. You can relate back to your own life as well.”

Similarly, books like Ring of Fire and Midnight on the Potomac examine the “grassroots perspective” of some of history’s most pivotal moments. Meanwhile, The Headache and Human History on Drugs show how everyday experiences like migraines tie us to the past in unexpected ways.

As Kean says, these kinds of books show a more relatable side to history, one that isn’t the realm of the exceptional moments or people. They not only help us connect with those who came before on a more personal level, but show us how we all play our part in the human story in ways that can be profound — even if our names are never the answer to a question on the test.

Keep reading,

Kevin

Between Quotations

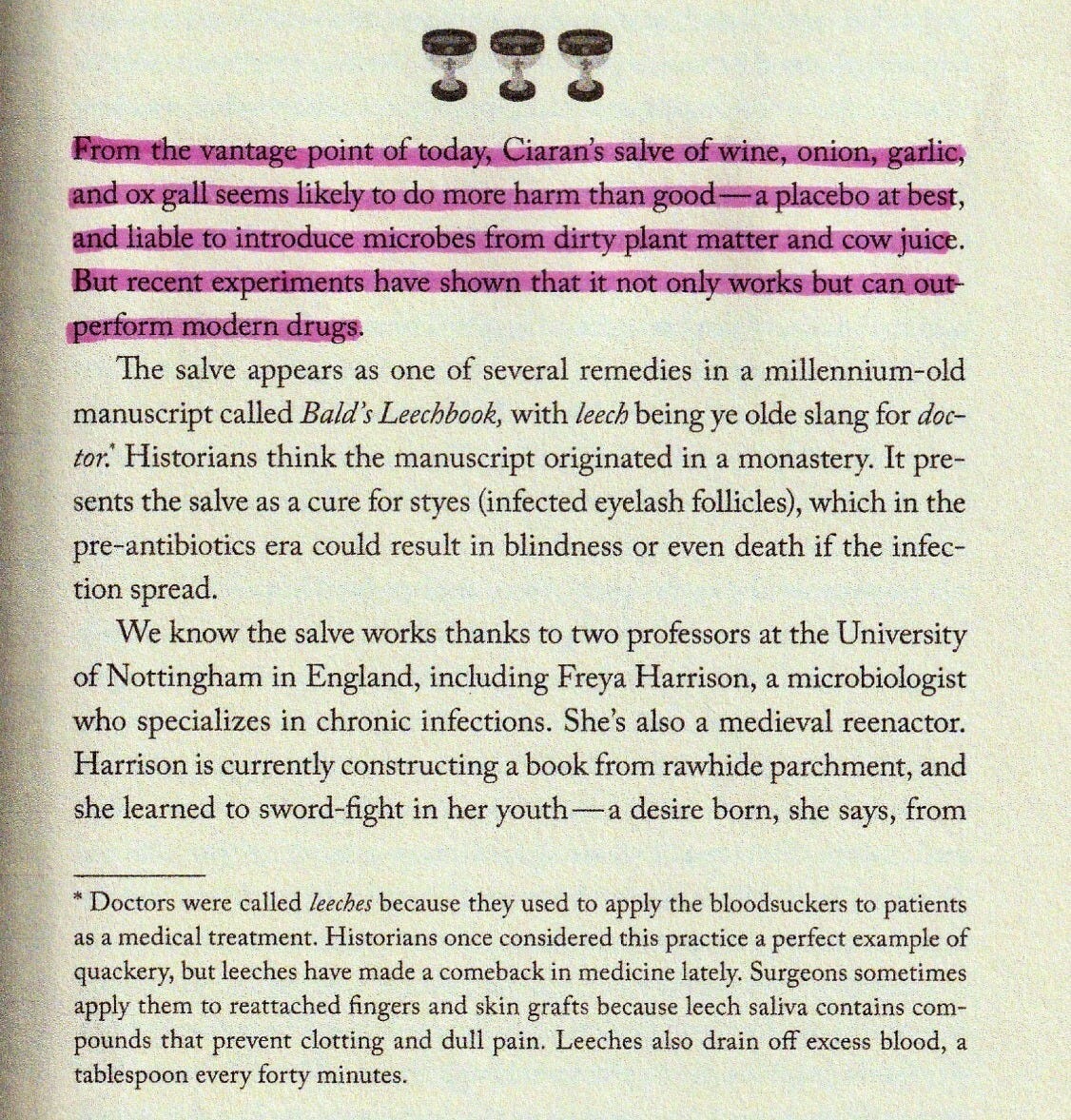

Many medieval cures — from smearing burned bees on a scalp to virgin-gathered waters from east-flowing rivers — are nonsense. However, researchers have tried this, erm, galling recipe and found it to have antibacterial properties. Kean even tried it himself on a toothache, to surprising effects.

In conversation with Alexandra Churchill & Nicolai Eberholst

Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August (1962) is a landmark title in World War I books; however, today, Tuchman’s narrative can seem a bit … disengaged. She presents the war from the perspective of distant decision-makers, such as generals and politicians, and that can sometimes feel like you're reading a play-by-play of history’s longest game of Risk.

For their new book, Ring of Fire, Churchill and Eberholst instead look at the war from its “grassroots perspective.” They chronicle the stories of soldiers, workers, students, and family members who experienced the war firsthand. In doing so, they rediscover the First World War’s truly global story:

“If you stripped away the national identifiers from many of the quotes in the book, it would be incredibly difficult to guess where the person was from. The way people express themselves in letters, diaries, or memories is all so similar across borders.”

Big Think regular Tim Brinkhof recently spoke with Churchill and Eberholst; here’s what he learned.

An existential gut check of a book

“What actually am I?” It’s the kind of question you’d expect to ask in existential philosophy 101 or during a particularly transcendental acid trip. It’s not something you’d expect to pop into your head while reading a book on the microbes living in your gut. But that’s precisely what happened to Jasna Hodžić while reading The Microbiome Master Key.

Hodžić explains: “The book challenged my assumption that my microbiome was made up of mostly passive passengers. Instead, the authors show that it is essential to almost every part of how we function: healing, sleeping, how our skin looks, and maybe even how we think.”

Hodžić sat down with authors Brett and Jessica Finlay, a father-daughter scientist duo, to chat about what the latest scientific research tells us about how our trillion-or-so microbial guests make us, well, us.

Recommended reads

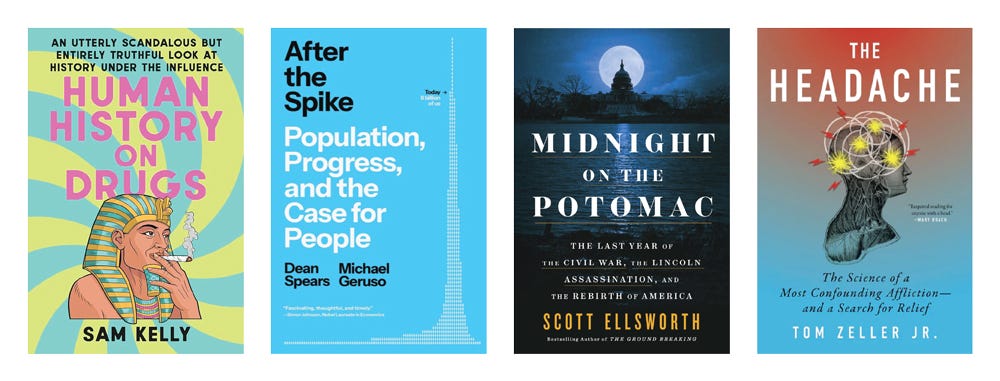

July was chockablock with odd and interesting history books to enjoy. Here are four we recommend checking out, and as always, if one sparks your interest, you can click on the link below to enjoy a preview over on Big Think.

1. Human History on Drugs

by Sam Kelly

Did you know Alexander the Great was Dionysian in his drinking or that Sigmund Freud enjoyed daily hits of nose candy? What about Vincent Van Gogh’s insatiable appetite for yellow paint? From the Priestess at the oracle of Delphi to Steve Jobs, Kelly dives into the role drugs played in the lives of history’s most influential figures.

2. After the Spike

by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso

The world’s population is projected to peak at 10 billion people by the mid-2080s. This forecast has led many to fear dire consequences for the environment and human welfare. But what if this catastrophizing has it backward? In this thought-provoking book, Dean Spears and Michael Geruso explain why depopulation would actually be worse for us and our world.

3. Midnight on the Potomac

by Scott Ellsworth

1865. The last year of the Civil War and a turning point in U.S. history. From a Confederate plan to burn down New York City to Lincoln’s almost doomed presidency and John Wilkes Booth’s connections with the Confederate Secret Service, Ellsworth shines a new light on the year America was reborn.

4. The Headache

by Tom Zeller Jr.

Why me? is a question familiar to anyone who has ever suffered a migraine. Unfortunately, scientists still don’t understand the underlying causes of this cranial affliction. Tom Zeller Jr. explores the history and mysteries behind the pain in our brains.

5 of the strangest books ever written

Sometimes I read a book that I can’t come to grips with, and I think, “Huh, that was a weird one.” But there’s strange and then there’s strange. These five books definitely fall into the latter:

Codex Seraphinianus by Luigi Serafini (1981)

Finnegans Wake by James Joyce (1939)

The Anarchist Cookbook by William Powell (1971)

Gadsby by Ernest Vincent Wright (1939)

Voynich Manuscript (early 15th century)

What makes these books such historical curios? Big Think regular Scotty Hendricks explains.

Kevin Dickinson is the books editor at Big Think. He holds a master’s in English and writing, and in addition to Big Think, his work has appeared in RealClearScience, Pop Matters, the Writer Magazine, and the Washington Post.

Check out more of Big Think’s content:

Big Think | Mini Philosophy | Starts with a Bang | Big Think Business

Your immersion experience, Kevin, reminds me of the field trips enjoyed with students. Going to see the butterfly migration, going to the bicycle shop to see how to maintain and repair, going to see how pizzas are made (and spun), going to see what first responders are needed to do in their work, in other words, experiencing realities beyond lectures of description. The fun of life is the opportunity to be a part and not always a bystander.

Experiences are memorable!