Welcome to Big Think Books, your direct line to the books and ideas that shape our world. I’m Kevin Dickinson, and this month, we’re investigating the Book of Books, the Bible. We’re also revisiting Stephen King’s most misused piece of writing advice, and we have some new book recommendations for you.

Next month, we’ll kick off summer with Agatha Christie, John le Carré, and even more classic reads. Stay tuned!

Gimme that (really) old time religion

Despite being raised in the church, I never felt God’s presence. I read the Bible, sang the hymns, and punctuated my prayers with amens, but where others felt divine love and something greater than themselves, I found only more questions.

When I was 12, I decided the best way to remedy this predicament was to make a public display of my faith and be baptized. So, in front of family, friends, and my congregation, I was dunked, ritually cleansed, and rose from the water to feel … nothing. No sense of the holy spirit descending, no coming-to-Jesus moment, not a single ray of symbolic sunshine piercing the overcast sky in a heavenly attaboy. Just a soggy uneasiness and the tang of stagnant pond water.

I’ve since grown distant from my childhood religion, but I’m still captivated by the Bible: its history, how its stories have been endlessly reinterpreted, and how it has influenced cultures and societies for 2,000 years. For those reasons, I decided to dedicate our May newsletter to the Book of Books.

Actually, “book” isn’t quite right. The Bible is more of a library, one that collects texts on subjects as diverse as myth, poetry, history, politics, philosophy, fictional narrative, and yes, religious edicts. Understanding these texts in their proper historical and cultural context often requires outside reading, so I was thrilled when I received a copy of Princeton historian Elaine Pagels’s new book, Miracles and Wonder.

In it, Pagels dives into the mysteries surrounding Jesus’ life: What really happened at his birth? What was his original message? How did later generations of Christians come to interpret his death? It may initially seem a simple puzzle, seeing as the Bible provides off-the-shelf answers. However, as Pagels makes clear, a careful reading of the Gospels reveals each provides different answers to these questions.

It piqued my interest so much that last month, I set out to discover what historians can and can’t say about the historical Jesus. I read books, listened to online lectures, and interviewed Pagels alongside Joshua Schachterle, a researcher and writer about early Christianity. I discovered that everything historians know about Jesus (with a high degree of certainty) can be squeezed down into a single sentence:

Jesus was a 1st-century itinerant Jewish preacher who spoke Aramaic and was crucified by the Romans.

Yes, I’m being playful here to make a point. However, it’s not as much of an exaggeration as you may think for reasons I explain in my latest post.

While I found this surprising, I probably shouldn’t have. I’ve always read the Gospels as a biography in four parts. I would blend the shared stories together and reason through the contradictions until I had self-edited my own unified theory of Jesus’ life. I think a lot of people take a similar approach, but after talking with Pagels and Schachterle, I’ve come to appreciate that these texts weren't written to be histories or biographies.

Instead, each anonymous Gospel author used the story of Jesus as a template and, through their retellings, shared unique theologies that spoke to the human condition — one of struggle and injustice, yes, but also a hope for a better future. It’s the reason I think these stories have appealed to believers and nonbelievers ever since. Scholars have researched and analyzed them. Authors have borrowed their symbols and themes for their own stories. And artists from painters to architects have resurrected them through new mediums.

I admit: When we approach the Gospels, and by extension the Bible, like this, the life of Jesus does grow blurry in its certainty. But in turn, it helps us view our shared humanity with a sharper focus.

Keep reading,

Kevin

Between Quotations

I knew I had to speak with Pagels after jotting this question in the margins of her book, Miracles and Wonder. She recommends we approach the Gospels as their own thing, a genre their anonymous authors called evangelion, or “the good news.”

Check out my latest article to find out why this approach can enliven and deepen our understanding of the Gospels.

In conversation with A.J. Jacobs

In 2006, A.J. Jacobs, known for his “immersion journalism” style of writing, took on a unique project: He decided he would follow the Bible as literally as possible for an entire year. He observed the Sabbath, learned to play a ten-string harp, and heralded each month by blowing a ram’s horn. This self-experiment resulted in his book The Year of Living Biblically.

We caught up with Jacobs to discuss his bestselling book, why it’s enjoying a second life in 2025, and the lessons his experiment taught him. As he told Big Think:

“The real divide here isn’t between religious and non-religious, but between rigid, absolute thinking and being flexible and open to different perspectives.”

You can read the interview here.

6 books that unpack the Bible and its history

While speaking with Bible experts and enthusiasts this month, I asked them to recommend books that would help readers better understand the Bible and its history. Here’s what they suggested:

The Rise and Fall of the Bible by Timothy Beal

How God Becomes Real by T.M. Luhrmann

Reading the Bible Again for the First Time by Marcus J. Borg

Heaven and Hell by Bart Ehrman

Scripting Jesus by Michael White

The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels

Click here to find out why.

In conversation with Jonathan Rauch

In a 2003 essay, journalist Jonathan Rauch celebrated the rise of “apatheism” and religion’s loosening grip on American public life. Today, Rauch calls the essay the “dumbest thing” he’s ever written.

In his latest book, Cross Purposes, Rauch argues he didn’t appreciate how Christianity and liberal democracy each helped stabilize American public life in the past, making it less culturally polarized and more politically functional.

As he told Big Think: “We live in a society which, on both left and right, has imported religious zeal into secular politics and exported politics into religion, bringing partisan polarization and animosity to levels unseen since the Civil War.”

Check out the full interview on Big Think.

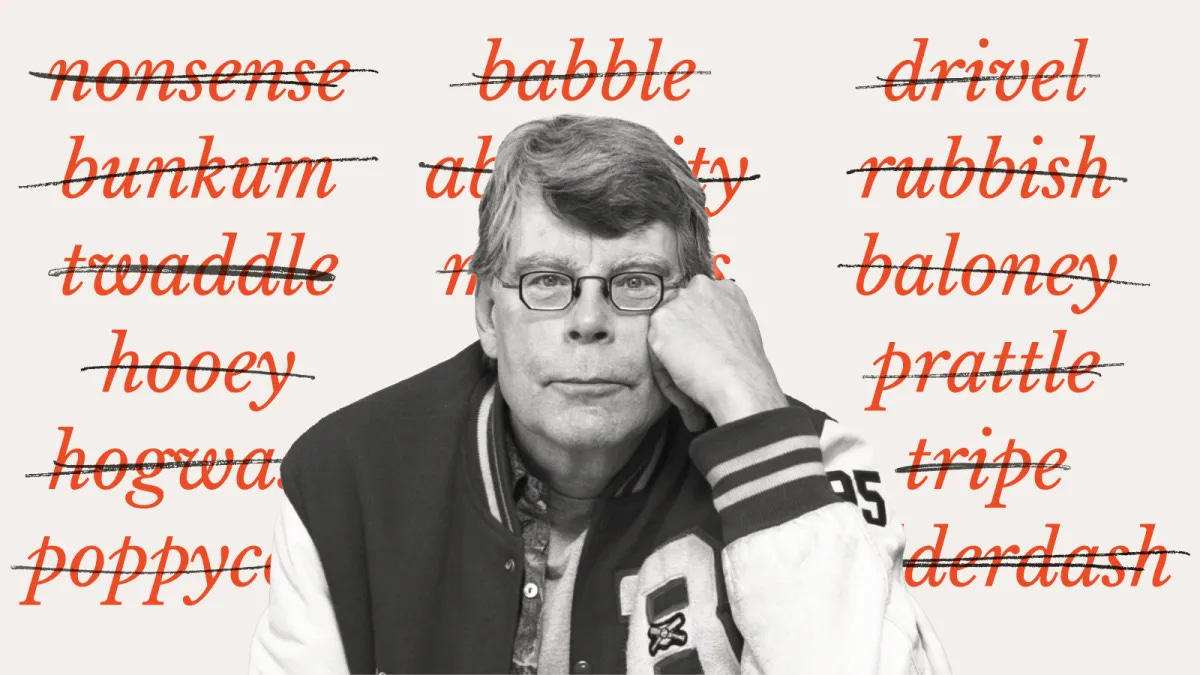

Stephen King’s most misused piece of writing advice

King has written a lot about his craft, but one quote of his always seems to make the rounds online:

“[T]hrow your thesaurus into the wastebasket. The only things creepier than a thesaurus are those little paperbacks college students too lazy to read the assigned novels buy around exam time. Any word you have to hunt for in a thesaurus is the wrong word. There are no exceptions to this rule.”

All respect to King, but that is nonsense (also bunkum, hooey, hogwash, twaddle, and poppycock). A thesaurus is no different from any other writing tool: Used incorrectly, and it sours good writing; used correctly, and it elevates your prose. I explain why this advice has become so misused.

Recommended reads

Looking for a smaller reading project than the Bible? Not a problem. We have four new book recommendations for you this month. Click the links below to enjoy a free preview.

1. The Creativity Choice

by Zorana Ivcevic Pringle

We all have ideas, so why don’t we bring more of them to life? Diving into the science of creativity, Pringle shows readers how to turn inspiration into achievement while avoiding self-made traps and misguided advice along the way.

2. The Neverending Empire

by Aldo Cazzullo

“The Roman Empire never fell," writes Cazzullo. Instead, Rome has traveled through the ages in the art, religion, and ceremony of European history. In this book, Cazzullo explores the Empire’s indelible cultural lineage.

3. Proto

by Laura Spinney

History’s most successful conqueror wasn’t a king or empire. It was a language. While Proto-Indo-Europoean hasn’t been spoken for thousands of years, its descendants have spread across the world to shape its history. Spinney reveals this lost language’s incredible story.

4. The Art of Change

by Jeff and Staney DeGraff

Jeff and Staney consider how true change doesn’t come from avoiding contradictions; it comes by embracing them. For this reason, they encourage creative thinkers to adopt a “paradoxical mindset.”

Kevin Dickinson is the books editor at Big Think. He holds a master’s in English and writing, and in addition to Big Think, his work has appeared in RealClearScience, Pop Matters, the Writer Magazine, and the Washington Post.

Check out more of Big Think’s content:

Big Think | Mini Philosophy | Starts with a Bang | Big Think Business

Try The Urantia Book... Digital version (Amazon) only $5!