Poetry, peacocks, and panic in the church basement

Matt Ridley takes on sexual selection to find out how deep the rabbit hole goes...

Welcome to Big Think Books, your direct line to the books and ideas that shape our world. I’m Kevin Dickinson, and this month, we’re celebrating one of the most important and controversial books ever written: Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Darwin not your thing? No worries. We’ve got you covered with a whole shelf of ideas, from the biomes you breathe to geopolitics and our anxiety surrounding anxiety.

Next month, we’ll explore the potential futures of science fiction (and our own timeline) with Hugo-winning author Ken Liu. Stay tuned!

Darwin drops an existential bomb

When I was 9, a youth pastor asked my Sunday school group, “If evolution is true, then why aren’t apes still evolving?” In hindsight, it’s apparent he hadn’t studied the evidence from reputable sources, nor was he asking a gaggle of grade-schoolers in hopes of an honest answer. No, his question aimed to seed a specific doubt in our young minds.

Put another way: If evolution is true, why aren’t apes becoming more human-like before our eyes? He may as well have wondered why zookeepers didn’t regularly arrive at work to discover their chimpanzee enclosures now housed troupes of very confused, very naked humans asking to bum a pair of pants and directions to the nearest bus stop.

None of this was apparent to my younger self, though. I took the challenge at face value and set out to discover why apes weren’t still evolving. Naive? For sure. However, my naivety led me to a lifelong fascination with Darwin and his theory of evolution by natural selection. I’ve enjoyed reading books on the subject ever since.

Today, I could answer my youth pastor’s question with more good faith than he posed it — and more confidence than a curious 9-year-old whose primary source on the matter was Pokémon.

Apes are still evolving. So are humans. While we are card-carrying members of the same order, humans didn’t evolve from modern chimps but share a common ancestor with our cousin species. My youth pastor’s mistake came from confusing the universal tree of life — with its boughs and branches expanding outward from deep Archean roots — with the Great Chain of Being — an ancient concept that views life as progressing linearly, with bacteria on the bottom and humanity standing tall at life’s pinnacle. And so on.

Also with the courtesy of hindsight, I now recognize that he was not questioning the evidence for evolution by natural selection. Not meaningfully. He likely didn’t harbor a similar icy rage against the Hubble constant, quantum mechanics, plate tectonics, or the germ theory of disease. His struggle was with the philosophical and spiritual fallout of the bomb Darwin dropped more than 150 years ago when he published On the Origin of Species (1859).

Actually, bomb may not be the right metaphor. In Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, Daniel Dennett famously described the theory as a “universal acid,” an idea so powerful that it “will eat through anything!” such that it cannot be contained. That life could result from a blind, algorithmic process doesn’t just reshape the field of biology. It dissolves those boundaries and seeps into our notions of ethics, creativity, psychology, cosmology, and human culture. It spreads to the very ideas of meaning and purpose. It leaves in its wake, as Dennett put it, “a revolutionized world-view, with most of the old landmarks still recognizable, but transformed in fundamental ways.”

Or, to borrow yet another metaphor from the poet Jericho Brown: The thunder scares even as the lightning helps us see.

So while I disapprove of my youth pastor’s actions, I can sympathize with his struggle. Even those who accept Darwin’s theory wrestle with its full implications, and many try to erect barriers to keep it from bleeding into, and subsequently souring, their favored landmarks. Instincts may stem from nature, but must ethics exist on a higher plane to be humane? If we accept evolved differences between the sexes, must we also accept reactionary politics and social policies? Is it evolution or culture that writes more indelibly on the human mind?

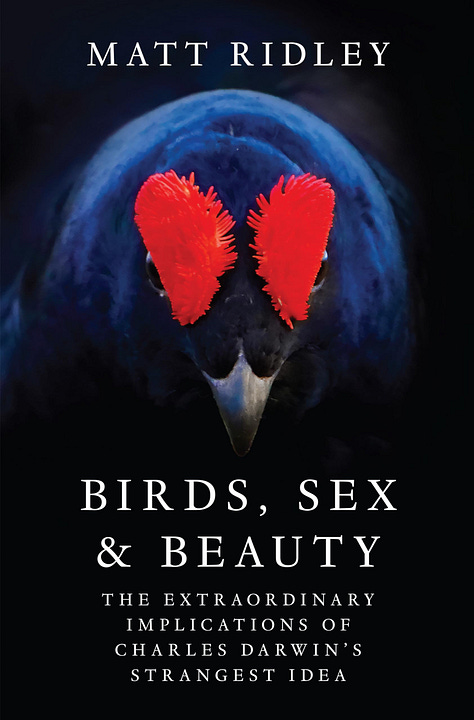

My latest read about evolution, Matt Ridley’s Birds, Sex and Beauty, steps into this fray by exploring Darwin’s other dangerous idea: sexual selection. In an exclusive interview with Big Think, Ridley discusses why mate choice not only explains the peacock’s fabulous train of feathers and the bowerbird’s bedecked love nests but perhaps also the equally flamboyant qualities of our species, such as art, humor, and music.

You can check out our interview and a preview of Ridley’s book below. This month, we also spoke to Carl Zimmer, author of Air-Borne, about the aerobiome, that “gaseous ocean” we all swim in and share with trillions of invisible life forms; Martha Beck, author of Beyond Anxiety, on how to avoid falling into an “anxiety spiral”; and Edward Fishman, author of Chokepoints, on how the United States changed the weapons and rules of economic warfare.

Keep reading,

Kevin

Between Quotations

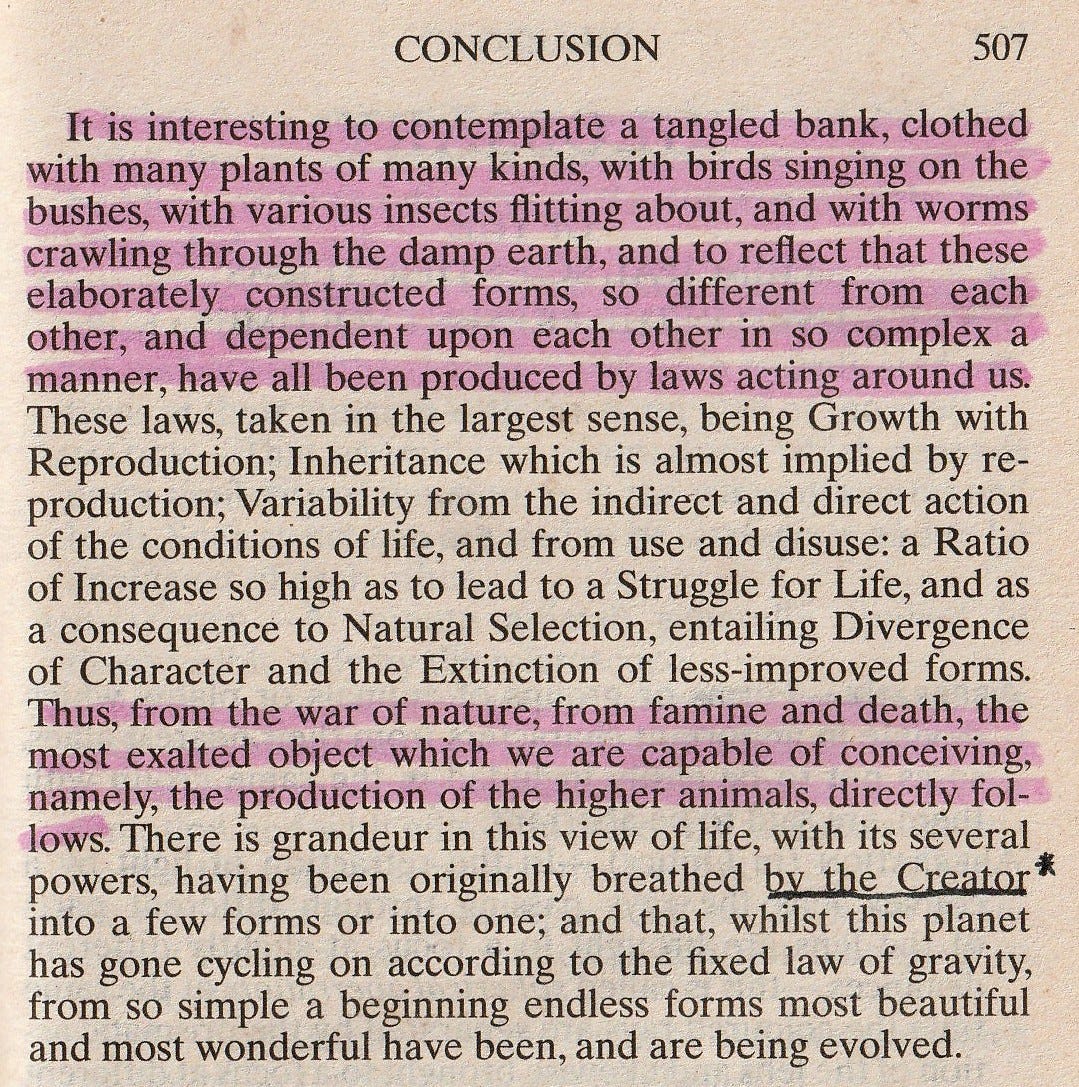

One of life’s joys is highlighting a passage simply because of the elegance of the writing. Sadly, it’s not a joy I associate with scientific books as often as I’d like. That’s not true when I read Darwin, though. Here’s one of my favorite passages, taken from the conclusion of On the Origin of Species:

When revisiting the passage, I learned that the phrase “by the Creator” was added only in the 2nd and later editions. Darwin did not include it in the original print run of Origin. That piqued my curiosity; I’ll have to find out why down the road.

In Conversation with Matt Ridley

What do art, feathers, and explosive penises have in common? Birds, of course. They also evolved through sexual selection — an evolutionary mechanism Matt Ridley calls “Darwin’s strangest idea.” While you may consider the mating rituals of the British black grouse or the nests of the Australian bowerbird to be separate from true “art,” that doesn’t mean sexual selection hasn’t had a hand in shaping humans in fascinating ways.

As Ridley told Big Think:

“When you think about things like wit and humor and song and poetry and art, none of these things seem to help you survive. They certainly wouldn’t have been much use in the African savannah for hunter-gatherers, but they help you get mates.

“Now, these traits may have another function which is more like natural selection in that they help you survive in a group and encourage others to like you. There’s a social brain hypothesis that is well-developed. But the sexual brain hypothesis has never really been explored adequately.”

You can read Ridley’s full interview here.

Recommended Reads

We featured a lot of brilliant book previews on Big Think recently. Maybe one of these will find its home on your bookshelf:

1. These Strange New Minds

by Christopher Summerfield

There is no shortage of AI books on the market, but those that explain how these algorithms work in simple, thoughtful prose remain a rarity. Thankfully, Summerfield does just that, such as when he describes why AI’s “sensory void” prevents these systems from developing real-world understandings (and what it would take for machines to see the world as we do).

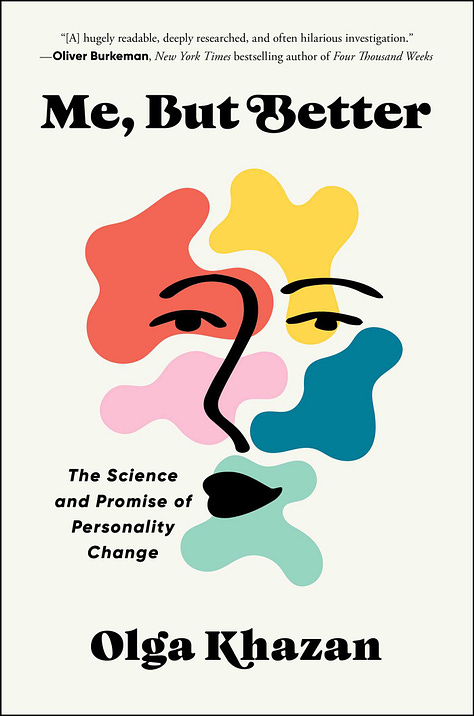

2. Me, But Better

by Olga Khazan

Many people believe their personalities are fixed, but research shows they evolve throughout our lives (usually for the better). In her new book, journalist Olga Khazan experiments with her personality to discover how to navigate the change.

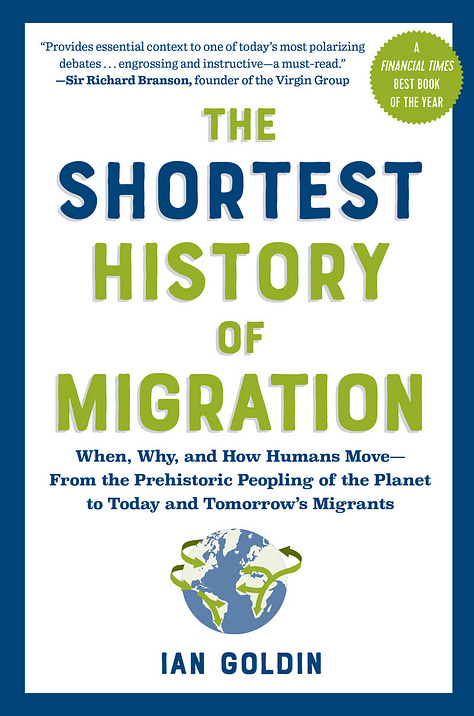

3. The Shortest History of Migration

by Ian Goldin

Goldin explores humanity’s history of migration, from our prehistoric first steps out of Africa to the mass migrations of the mid-19th century. He also tackles the important discussion of why migration statistics should be regarded with wariness and scrutiny, especially when they serve simple political narratives.

4. Tiny Experiments

by Anne-Laure Le Cunff

Instead of seeing life as a series of checkpoints to reach, Big Think alum Le Cunff wants us to approach it with an experimental mindset and a sense of self-discovery. Disruptions will happen, of course. When they do, she recommends cultivating “active acceptance” to adapt and overcome.

5. Money on Your Mind

by Vicky Reynal

Reynal investigates the beliefs and emotions that drive — and sometimes sabotage — our relationship with money. But it’s not as simple as separating the good feelings from the bad, as we see in her survey of humanity’s ever-evolving relationship with greed.

6. Birds, Sex and Beauty

by Matt Ridley

Nature or nurture? What are we born with, and how does our environment shape us? It’s a good question that too often leads to flawed, either-or answers. Matt Ridley answers that the two work together in surprising ways.

5 books that changed our understanding of the origin of life

Traditionally, people believed that life on Earth required a divine spark to get going. This month, we look at five books that built the empirical case that life’s origins differ from those of myth and legends. They are:

Theory of the Earth by James Hutton (1788)

On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin (1859)

Experiments in Plant Hybridization by Gregor Mendel (1865)

What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell by Erwin Schrödinger (1944)

Cosmos by Carl Sagan (1980)

Why did these five make the cut? Big Think regular Scotty Hendricks explains.

Kevin Dickinson is the books editor at Big Think. He holds a master’s in English and writing, and in addition to Big Think, his work has appeared in RealClearScience, Pop Matters, the Writer Magazine, and the Washington Post.

Check out more of Big Think’s content: Big Think | Mini Philosophy | Starts with a Bang | Big Think Business

I’ve just started listening to a recording of Christopher Summerfield’s - These Strange New Minds. It’s a completely absorbing book. (And the narrator is excellent too!) A great recommendation Big Think Books, thank you!

Thanks, Kim. I thoroughly enjoyed Summerfield's book and am glad you're enjoying it too. Best!