Welcome to Big Think Books, your direct line to the books and ideas that shape our world. I’m Kevin Dickinson, and this month, we’re celebrating the potential futures of science fiction (and perhaps our own timeline). We also have a bevy of new book recommendations for you and a dive into the weird history of simplified English spelling (a spelling system that is, let’s face it, weird enuf enough already).

Next month, we’ll examine the history of the Bible and its 2,000-year influence on Western cultures. Stay tuned!

Found in translation

I’m always curious why people are drawn to read the stories they do. Sometimes, there’s little to wonder over. Romance and erotica are best-selling genres for obvious reasons. Other times, I believe I have a decent grasp on things. Literary fiction allows us to peek behind the curtain of solipsism to experience life outside our own heads, while mystery pairs our morbid fascinations with the desire to live in a world where justice prevails (if only we can piece the clues together).

But one genre I have always puzzled over is science fiction. Why is it that so many fiction fans, myself included, find these stories so enticing? Ever since Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) — and arguably even before that — readers have enjoyed exploring the genre’s forbidden technologies, alien planets, and far-flung futures. Yet, when compared to the genres mentioned above, science fiction seems so distant, so disconnected from the lives we live and the reality we live in. So, what’s the point?

One possible answer is that science fiction serves as a preview of the future; its authors either predicting or inspiring the events and technologies that come to change the world. I’ve never found this answer satisfactory. For one, it confuses these stories’ literary symbolism for literal schematics. For another, it’s only with the courtesy of hindsight and cherry-picked examples that it seems plausible. As a whole, the genre beats the prophetic market no better than Nostradamus or Miss Cleo.

Another possible answer is that science fiction investigates the consequences of scientific findings and technological advances through fictional thought experiments. This answer certainly applies to some stories, but it doesn’t come close to describing many others: Dune (1965), The Martian Chronicles (1950), and, of course, Buck Rogers (1929) all buck this trend.

Is it escapism then, pure and simple? Sure, but this answer feels unsatisfactory when considering the genre’s great works: Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1985), and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968). I could go on, but you take the point. There’s something more going on here.

This question was top of mind as I read two new Big Think articles this month. The first was by Ken Liu, the Hugo-winning science fiction author and a translator of Chinese works such as Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem (2008). There’s a moment in Liu’s article where he experiments with using AI to translate a Classical Chinese poem. With each translation, he asks ChatGPT to change its agenda while playing as a translator. With each ideological conversion, the poem subtly changes both its symbolic language and its implied message.

That struck a chord with me while reading our interview with Mike Duncan, host of the Revolutions podcast. Duncan’s latest project is pure science fiction: a story of the Martian Revolution that weaves the common threads of actual uprisings into a future history. The story resembles similar ones told by other authors — say, Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars (1992) or Robert Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (1966) — but Duncan’s ideas about history and the human condition translate its symbols and message differently.

It reminded me of another potential answer for science fiction’s appeal: It’s not about the future at all. Like any genre, it offers a language of symbols that allow writers and readers to explore ideas. Those ideas can be about the past and the present as much as the future. It can explore our personal fears, hopes, beliefs, experiences, and longings as much as our social and cultural ones. Far from being distant and disconnected from our lives, science fiction provides a unique language in which we can share it.

Keep reading,

Kevin

In conversation with Mike Duncan

Podcaster Mike Duncan has chronicled history’s most significant revolts: the French Revolution, the Bolshevik insurrection, and the Spanish-American Wars of Independence. In his podcast’s latest season, he explores the bloody uprising that will (maybe, one day) stain the Red Planet redder: the Martian Revolution.

As he told Big Think:

“There are archetypes that recur throughout history. Liberal elites seeking reform, educated professionals whose political power doesn’t match their social status. Revolutions involve civil wars, foreign interventions, and the interplay between these elements. That’s what I used to build the story.”

You can read the full interview on Big Think Books.

From the cinematograph to the “noematograph”

Paris. A cold December night in 1895. A line of Parisians pay a franc to enter the Salon Indien du Grand Café, where they are introduced to a technological wonder: the cinematograph. They become entranced as they watch women leaving a factory after a day’s work, men disembarking from a ship, and a young girl playing with goldfish — moments of life captured on film and replayed on a blank white screen. The world’s first movie night.

But did these lucky Parisians recognize that they had just witnessed the birth of a brand-new artistic medium? Probably not.

Ken Liu opens his latest article with this vivid scene to ask us a related question: Are we similarly witnessing the birth of a new artistic medium in AI? As he writes:

“When it comes to AI and art, we’re still only at the moment when all we can see is a flickering horse-drawn bus coming toward us. Much more playing, experimenting, critiquing, and, most importantly, failing, will be required to invent the language of AI as a medium for art.”

It’s a provocative question, one Liu asks us to explore alongside him.

Speling iz difikult, izn’t it?

English spelling is painfully inconsistent. Why does tomb rhyme with groom but not comb? Why does the EA combination have so many unique pronunciations (weak, bread, break, earth, and heart)? And don’t get me started on those silent P’s, K’s, and G’s welded to the front of seemingly random words.

Why has nobody fixed this mess and simplified English spellings to make things easier for children, newcomers, and writers whose unending professional embarrassment is their habit of constantly mispelling words by misteak?

Many people have tried: Benjamin Franklin, Andrew Carnegie, Mark Twain, Theodore Roosevelt, and — the man whose name is synonymous with the dictionary — Noah Webster. Yet despite their successes elsewhere in life, they all failed to reform English spelling.

We spoke with Gabe Henry, author of Enough Is Enuf, to find out why. As we dove deeper into his “biography of futility,” we discovered some important lessons on the nature of language and the passion people have for how they choose to share their voices with others in print and across time.

Recommended reads

Having trouble finding your next book? We’ve got you covered. Here are six recommendations, and to help you choose, you can click the links below to enjoy a free preview.

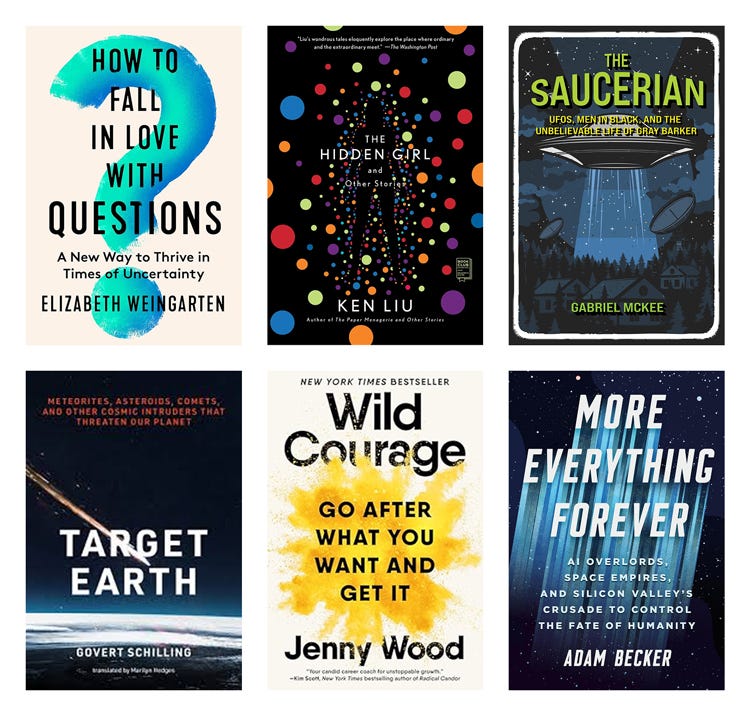

1. The Hidden Girl and Other Stories

by Ken Liu

This short story collection features Liu’s “Singularity” hexology, a series of stories that take place in a world of uploaded minds and all-powerful AI. These stories served as the basis for the cult TV show Pantheon, and you can read the first one on Big Think.

2. How to Fall in Love with Questions

by Elizabeth Weingarten

It’s a pleasant feeling to know the answer, but journalist Elizabeth Weingarten wants us to embrace questions with just as much passion. Or as the poet Rainer Maria Rilke put it: “[T]ry to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms, like books written in a truly foreign language.”

3. Target Earth

by Govert Schilling

Disaster struck 66 million years ago when a 6- to 10-mile-wide asteroid collided with Earth, an event that triggered our planet’s fifth mass extinction. In this book, astronomy writer Govert Schilling investigates the science of asteroids, meteors, and comets; their potential dangers; and the positive outcomes resulting from Earth’s frequent cosmic visitors.

4. The Saucerian

by Gabriel Mckee

Gray Barker’s eccentric personality and love of entertaining stories led him to start Saucerian Books, an imprint focused on UFOs and paranormal phenomena. In Mckee’s telling of Barker’s story, readers discover why a skeptic became a hoaxer and how fantastical stories can slowly, but inseparably, blend into reality for those who want to believe.

5. More Everything Forever

by Adam Becker

Becker investigates how Silicon Valley billionaires are trying to reshape the future in their image — an image often based on pseudoscience, untested optimism, and bizarre misreadings of classic science fiction.

6. Wild Courage

by Jenny Wood

We are taught to suppress our obsessive, reckless, manipulative, and weird personality traits. Ex-Google executive Jenny Wood wants us to reexamine these traits so we can go after what we want in life without fear.

5 science fiction novels written by scientists

What happens when scientists take the age-old writing advice “write what you know” to heart? These five delightful tales:

Nightfall by Isaac Asimov (1941)

Timescape by Gregory Benford (1980)

Contact by Carl Sagan (1985)

A Door into Ocean by Joan Slonczewski (1986)

Blindsight by Peter Watts (2006)

How did their scientific backgrounds influence their fictional worlds? Scotty Hendricks dives in to find out.

Kevin Dickinson is the books editor at Big Think. He holds a master’s in English and writing, and in addition to Big Think, his work has appeared in RealClearScience, Pop Matters, the Writer Magazine, and the Washington Post.

Check out more of Big Think’s content: Big Think | Mini Philosophy | Starts with a Bang | Big Think Business

Ah, that Asimov!!-- he was a genius, and he had the sideburns to prove it!! 👍😅